What role do legumes play in the emerging food security crisis?

First, let’s establish some facts about the current food crisis.

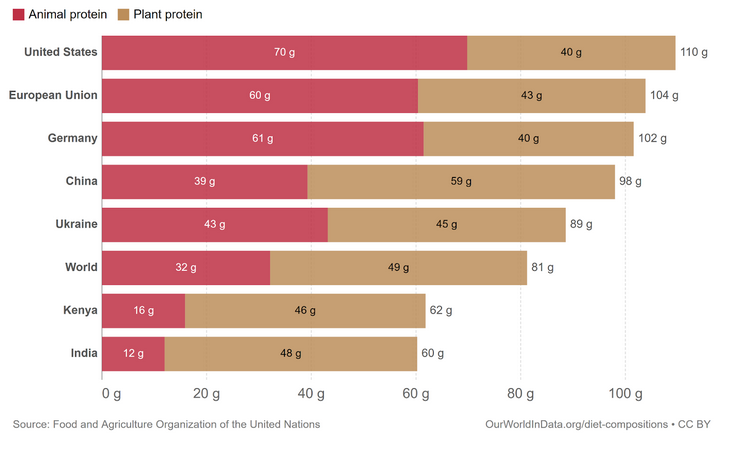

With overnutrition globally becoming a bigger problem than undernutrition, there is no shortage of food. However the price of food commodities like wheat, maize and soybeans closely follows the price of oil, and is subject to speculation. And yet, 36% of the grains are used as animal feed: western countries need to shift protein consumption towards more plant-based food, with Kenya and India being an example of a better ratio to attain.

In terms of plant-protein, the most cultivated legume in Europe is soy. Leopold Rittler from Donau Soja started by thwarting some of the clichés we might have on soy – that it is full of GMO, and that it leaves environmental destruction in its path: in Europe, only GMO-free Soy is allowed. It doesn’t require fungicide or insecticide, and organic soy production has almost the same yields as conventional one.

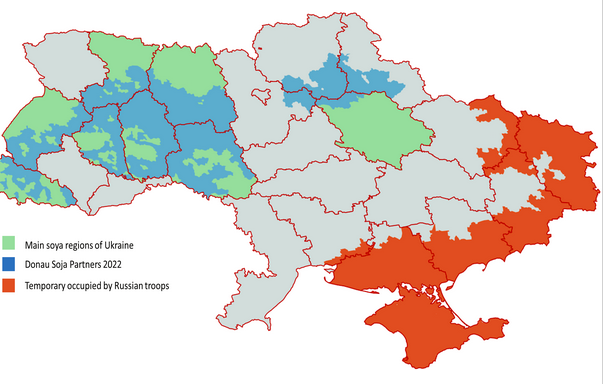

Ukraine does have a special place as a regional producer: ⅓ of European soybean production takes place there. With the soy fields located in the western part of the country, away from the occupied regions in the east, the situation is not as catastrophic as with other crops like sunflowers, and farmers have been going to the fields despite the war. The challenges however lie in the export: the land routes are not yet established enough to compensate for the blockade of Black Sea trade routes.

In India, as reported by Lopamudra Sahu from Edible Routes, the government is working on interventions focusing on pulses. Through their high nutritional value, and their role in resilient agriculture, pulses are a key component in fighting against malnutrition in children and high prevalence of anemia in women. As a result, India has seen a growth of 91% in pulse production, from 13.38 million metric tons in 2005 to 25,58 million metric tons in 2020-2021.

Kenya is also facing hunger, according to Daniel Wanjama from Seed Savers Kenya. The price of food commodities is up by 50%, and 3.1 million people in the nodmadic regions in the north eastern-part of the country are facing starvation. The fuel crisis but most of all drought, has made farmers unable to produce enough, sometimes sowing up to three times without any harvest.

Legumes are an important part of the Kenyan diet, but they also face challenges: the seeds are unavailable in shops, and seed companies don’t allow farmers to share or trade seeds, even though it is traditional. On the plus side, legumes are now recieving attention from stakeholders, and there is a lot of advocacy on increasing legume production.

Want to learn more? Rewatch the Talk:

- For any questions contact Lisa Hoffmann via

- Find out more about the Global Bean project and its 40 partners from 15 countries

- Register for the global bean project’s monthly newsletter